We slept in again as Groundhog Day dawned, and looked forward to our walking tour of Santiago – the only thing we felt comfortable doing given the COVID risk of not making our Antarctic expedition. We enjoyed a leisurely wake up, but this time both actually making it to breakfast before the 10:30AM cut off (a very civilized cut-off time for breakfast if I do say so). The breakfast was unfortunately indoors that morning because they were cleaning the usual outdoor area, but we were able to grab our food and still find a table on an outdoor patio. The clean tong/dirty tong baskets and process was still in effect thankfully.

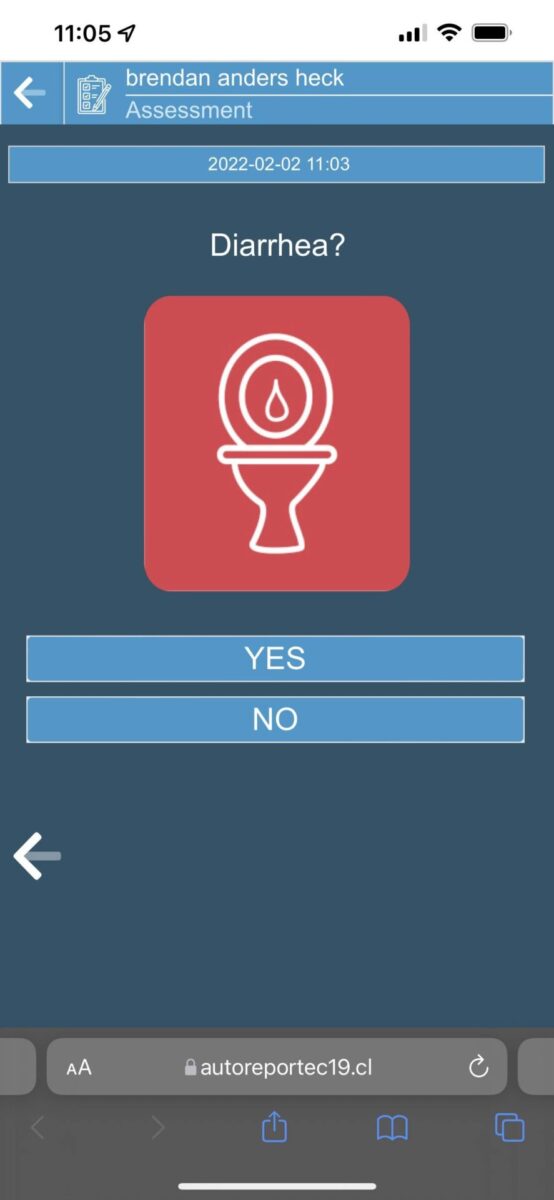

We also performed our requisite Covid check-in through the Me Vacuno app, and wondered if anyone would actually report they had Covid through this channel. And what happened if you actually did? We did find the pictograms clever and hilarious.

After breakfast, CJ had one early afternoon call, and then around 1pm we headed out to walk to our free walking tour of Santiago.

We had checked Google maps, and it told us that it would take 45 minutes to walk to the meeting spot for the walking tour in Santiago that started at 2PM. So, we started at a leisurely pace in the same direction we headed in the previous day by the river, and with plenty of time to get there, but soon found it was a long long walk. While it was great to see a bit more of the city, by the end of the time we were fast walking to try to make it in time. We arrived right on time, but hadn’t allowed ourselves any extra time to find the actual meeting spot, so we walked around in circles a bit, but did eventually find it two minutes after 2PM. Not ideal from how I like to do things, which is if you aren’t early you are late, but thankfully we weren’t the latest to show up for the tour, and as we found in our walking tours in Europe, there was usually a halo period of at least 5-10 minutes before the tours would head out. Note to CJ – never wear flip flops for a walking tour.

We met our guide Israel, who was actually from Brazil, but had been living in Santiago for 7 years at this point. He said that he had been giving these tours for a few years now, but had only started giving them in English 3 weeks previously. As we found, he sometimes paused or fumbled looking for the right word, but he was definitely fluent in English, and gave the tour with no problems. It was a small tour with only two other people joining us.

One was a teacher from Indianapolis, who had been teaching at international schools abroad for many years. She had recently moved from Argentina, but lived in Santiago now. She had decided to finally do a tour of her own new city after having lived there for 6 or so months already. As we’d later find throughout the tour, she was one of those types who is VERY engaged, almost too much, she asked a bit too many questions, reacted almost as if she was doing outsized reactions for her class, and too often interjected her own thoughts or experiences of Chile/Santiago, that at times competed with Israel’s narration of the tour. I believe she meant well, but it definitely irked us, seemed to irk Israel, though he hid it well, and ultimately might be a reason why you shouldn’t go on tours of your own city. Best to leave the guiding to the tour guide.

The other woman who joined us was much quieter, we barely heard a peep out of her, but she was a young woman from the south of Germany, and was in Chile a month early prior to an internship starting.

The walking tour of Santiago can be summarized as just being okay. Israel did a pretty good job, but most of it was just historical and architectural facts thrown out at us, with less of the stories, mini quizzes, and questions for the group like we had seen by the best guides on our recent trip in Europe.

We started across from the Teatro Municipal de Santiago, the local theater. It was a pretty building and one of the older ones, but nothing too spectacular.

Across from the theater was a statue of four boys that had been gifted to Chile from Argentina upon Chile’s independence. The boy in front represented Chile, with Argentina representing a boy immediately behind potentially pushing the Chile boy, and two other boys more in the back that represented Peru and Bolivia, or essentially all the countries that bordered Chile. Bolivia was sort of pushing Chile over, which was symbolic of the time period it represented.

We then headed to the Plaza de Armas, which was the main square of Santiago. It was a very busy place with a lot of people milling about, even on a Wednesday. Israel took some time to talk to us about the founding of the city by the Spanish, and their dealings with the indigenous Mapuche people, which was atrocious just as any other country colonized by the Europeans, or really any colonized country for that matter.

A bronze map of the city in 1712 was inlaid into the ground in the plaza, and Israel used this as a way to explain some of the local neighborhoods, including Barrio Bellavista, which was just across the river. It sounded like a great place for nightlife and apparently rooftop bars and restaurants, but he often repeated the frequency of pick pocketing, and given that it sounded like where a lot of people would be, we decided ultimately it was too high of a Covid risk and didn’t end up heading there during our stay.

A statue of the Spanish conquistador Don Pedro de Valdivia was also in the plaza astride a horse, and the horse was meant to represent Chile. This was a gift from Spain upon Chile’s independence, but also seemed to be sending a mixed message, with the image of a Spanish conquistador riding and in control of the reigns of Chile. Possibly a passive aggressive gift from Spain?

Israel also spoke to us about another statue in the plaza called “Al Pueblo Indigena de Enrique Villalobos”. Rising 26 ft tall, it was meant to be a gift to the Mapuche indigenous peoples, and is composed of three elements: a seed, vegetation, and a human face meant to represent a Mapuche man. However, because the face is broken, and it was unveiled on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, you can probably guess how the reception to the statue went. It is much derided still to this day.

And, your requisite street performer also populated this main square on our walking tour in Santiago.

Also in the plaza was the Santiago Metropolitan Cathedral, but not the original. This would end up being a common refrain in Santiago, as many buildings were not original due to earthquakes, which are common to the region. Residing within the ring of fire which encircles the pacific and places like California, Japan, and New Zealand in addition to Chile, the region is known for its tectonic activity resulting in active volcanoes and common earthquakes. Because of this, many of the buildings in Santiago have been destroyed and rebuilt over the centuries. We noticed that most of the older buildings weren’t very tall, and this may be the reason that the architecture in the city wasn’t as exciting as we have seen in other parts of Latin and South America. Because of the miles of coastline of Chile, not only are earthquakes a problem, but resulting typhoons also are as well, and Israel took a brief detour to talk to us about what to do during a tsunamio (head away from the ocean and to higher altitude) and noted that all of the coastal cities also had tsunami warning systems and marked escape routes. What Santiago has also started to do with buildings that were destroyed, was to keep and/or reinforce any facades of old buildings that were still intact, but to add modern buildings onto or behind them, so that you end up with a pleasant mix of the old and the new.

We next stopped by a few museums. The Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino and the Congreso Nacional de Chile sede Santiago. The first was a prehistory museum that housed the oldest intentional mummies in the world. They were up to 7,000 years old, whereas the ones in Egypt are said to “only” be about 5,000 years old. This was a pricey museum by Santiago standards, but they still only charged 5,000 Chilean pesos, which is about $6. The second museum had originally been the national congress, but the congress had since moved, and the building was now a museum, but Israel didn’t really try to “sell” us on that one.

Next on the walking tour of Santiago was the Plaza Montt Varas or the Plaza de la Justicia, named after Manuel Montt and Antonia Varas. Montt was a lawyer by profession, and became president of Chile changing the face of the country through setting up various ministries, municipality laws, and civil code. Varas was his right hand man, a multiple time senator, and Montt’s Minister of the Interior. Together they fueled an export boom that led to technological development, expansion of cities and ports, and expansion of education. Linked closely as friends during life, they reside eternally together in the statue, and as named streets running parallel to each other that were close to our hotel. CJ has previously visited Puerto Montt, on Chile’s southern coast, founded after Manuel Montt.

We then headed south to La Moneda Palace. Officially the office of the president, but actually Chile’s presidents could reside wherever they wished, so few used the palace. For instance the recently elected President Boric was from Punta Arenas, and Israel believed he was still running the country from his residence there at the time. An interesting concept and one I can understand in our increasingly remote and “work from home” connected world.

To me this was our most interesting stop, as Israel delved into the history of the palace and one of it’s most famous occupants in Salvador Allende, a socialist president during the 1970s who had sought to nationalize major industries such as education, health care, but most notably copper mining. Up until this point US companies had had a foothold in Chile copper mining, and they and a lot of Chileans were making a lot of money doing so. Initially Allende’s policies led to decreased inflation in 1971, improved salaries, and higher education, especially increased literacy for those in rural areas. However, his policies were opposed by businessmen, employers, the Catholic church due to the increased education (can’t have churchgoers without ignorance!), and increased racial tensions between the indigenous people, who supported Allende’s reforms, and the white elites. The US also backed campaigns to fund worker strikes, because it was unhappy with Chile re-establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba. While initially Allende realized some success, by 1972 inflation had again risen up to 150%. On September 11th the Chilean military under general Augusto Pinochet aided by the US and the CIA staged a coup against Allende. They surrounded the palace with tanks and demanded that Allende come out and surrender otherwise they would rain artillery on the palace. Allende did not come out. An air raid that was televised throughout the world began as Allende gave a farewell radio address. The palace was bombarded and when the dust settled and the military entered the palace they found Allende dead by suicide. As Israel made clear, this was the military’s version of events, but some in Chile still wondered if the military didn’t actually gun him down and stage the suiced (note: an investigation in 2011 however did seem to scientifically prove the death was a suicide). After the coup, Pinochet took power and stayed in power from 1973 to 1990. Toward the end of his reign and due to increasing international pressure he held a referendum in 1988, which resulted in a vote 55% to 45% in favor of him stepping down, though that took him another 2 years to fully do. Interestingly enough a similar breakdown had just happened in the recent election with 55% favoring the socialist Boric versus 45% favoring the right leaning Kast.

We continued the walking tour of Santiago through Chile’s stock exchange area, an area with European architecture from the 1920s called appropriately Barrio Paris-Londres.

Around that area, two kind samaritans walking by along with our guide all commented to CJ to put her camera away due to pickpockets. It was a bit surprising since we have been to areas that seemed far more dangerous or sketchy than Santiago, but when a local goes out of their way to give you advice, you listen, and CJ did as they advised. This was something else we found about the Chileans, was that they were very collectively oriented, whether looking out for CJ’s camera, or all wearing masks outside to collectively protect against Covid even in the outdoors.

We ended the tour peaking our head into the Church of San Francisco, the oldest church in Santiago dating back to the 16th century, walking around half of Santa Lucia park, and parted ways with Israel in the Lastarria neighborhood.

He gave us a lot of great recommendations of places to try for dinner or drinks, and specialty food and beverages to try, but that will have to be on our next trip to Santiago, as we were running out of time and had even more constraints on what we felt we could do while being Covid safe.

We took a taxi back to the hotel so that we could get back in time for another work call that CJ had. We weren’t up for another 1 hour trek after the first one and 2+ hours of the walking tour. Even that was an argument about Covid risk management and exposure. Interesting times we live in.

CJ again worked late into the night, and then we walked over into the same neighborhood where we had dinner the night before. This time we stopped at Fuente Chilena for sandwiches to go.

We brought the sandwiches back to the hotel, but first stopped at the bar for libations to take up as well. We ended up starting with some Guayacan microbrew beers, with CJ having the better Golden Ale, and me having the still good Stout. For sandwiches, I got the Fricandela with Wagyu beef and CJ got the Ave with chicken, both of them “completa” or complete with all the fixings including Chilean Mayonnaise. My first bite was heaven and I immediately started postulating if a sandwich spot like this would go well in Denver. However, in subsequent bites my enjoyment waned a bit, and I eventually decided that the sandwich could be stellar, but needed a better ratio of all the ingredients together. As it stood, it was a bit too meat forward for my tastes. CJ liked hers even less, and felt like her sandwich smelled and tasted too much like chicken, if that makes sense. It may just be because we are used to “watered down” industrialized pumped full of antibiotics American style chicken, and this could in fact be how chicken should taste, but it was still a change for us. We paired both with fries, and after our meals washed it all down with a different Austral beer than we had had the first night. This one was a Calafate Ale, and had a berry flavor. It was an acquired taste, but one we grew to enjoy.