After a great first night in this diamond in the rough of a city, we were feeling the East meets West vibe woven throughout the history of Sarajevo. Unfortunately, we did not get great sleep because as mentioned previously, no hotels in the region seem to have air conditioning, and you either have to open the windows to get a breeze but suffer noise (and rain), or keep the windows closed and be hot.

The buffet breakfast at Hotel Sana was good, but nothing near the spread at Hotel Vardar. We had a fairly early start as far as early starts go for us (0900) so that we could meet up with a free walking tour at 1030 in front of the National Theater. There are many free walking tours on offer in Sarajevo, so just look through Trip Advisor to find the one that meets your schedule and your choice of topic. We opted for the general overview “East meets West” tour through Neno and Friends, although we were seriously considering the “War scars and new times” walking tour at 1545 with the same company. Ultimately we wanted to get out early, especially with the anticipation of poor weather in the afternoon.

We arrived in the designated square a bit early and had some time to chill. Here’s a view of the mountains from the square, with Soviet Bloc architecture looming large.

Neno himself (the owner of the tour company) arrived just with a moment to spare until start and we all gathered round and introduced ourselves. He explained that traffic in Sarajevo was getting worse and worse. In our tour group there was another American (here on vacation while his wife was in Sarajevo on business through USAID), a Malaysian man, a Vietnamese woman, a British man and a Nigerian woman. All solo travelers except for us! It turned out to be a great group.

Neno started off by giving a general overview of the history of Sarejevo from the square.

The history of Sarajevo goes something like this. An ancient Neolithic civilization, the Butmir culture, disappeared in 2400 BC. The next civilizations coming through, similar to Croatia, were the Illyrians and then the Romans as a province of Dalmatia. After that, like everywhere else in the Balkans, came the Slavs, and a little bit of Catholicism snuck in with the Eastern Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. But by and large, Sarajevo is an Ottoman city, the modern city being founded by the Turks in the 1450s. Many of the citizens converted to Islam during Ottoman rule, since it was pragmatic to do so – freedom of religion existed, but any non-Muslims were simply taxed more. In this tolerant environment, many Jewish and Eastern Orthodox people also found freedom and emigrated in.

The decline of the Ottoman Empire gave way to the Austro-Hungarians in 1878 after a battle took place in Sarajevo. You can see the influence of the Austrian architecture in many of the building around Sarajevo, and the re-introduction of Catholicism (see the cathedral on the right). The building on the left is a gynmasium, or school, established in that era, introducing Latin into the academic system.

We continued on to learn more about the Jewish history of Sarajevo, walking over to the largest and only functioning synagogue, the Sarajevo Synagogue, built in 1902 by the Ashkenazi Jewish community. It replaced a synagogue built in the 16th century during Ottoman rule by the Sephardic Jews, who found refuge in Sarajevo during the Spanish Inquisition. As mentioned previously, the Ottoman Empire tolerated all religions and influenced conversion through taxation. Most of the Jews composed the merchant and professional class and could afford to pay, and didn’t convert. Ashkenazi Jews began to arrive in the 19th century. All other synagogues besides this one were destroyed throughout the wars of the 20th century, and most Jews emigrated or were killed. The 20th century was an unusual period of conflict in a city that otherwise saw Muslims, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and Jews living in peaceful coexistence for hundreds of years.

We took a pause in the tour on the bank of the Miljacka river to further discuss the position of Sarajevo as the “Jerusalem of Europe”, and also delve in to the clash between communism and religion. Neno also explained that most of the wealthy families in Austro Hungarian times had residences along the river, and that this was a shift from Ottoman times, where people lived in the hills. The place for private life in Islam led to a separation of business from residences, whereas in Austro-Hungarian times and in Christianity itself, people so no need to separate their private and public lives and preferred to live above their businesses. This shift took place in the 19th century and still exists in Sarajevo today even though the majority of the citizens are Bosniak.

We then visited what Neno described as the “ugliest building in the city”, a Communist apartment complex built right before the 1984 Olympics in bold and vibrant colors to show the world that Communist architecture didn’t have to be drab. Drab is certainly not the word I would use to describe it. Tacky came to mind, but I have to admit I kind of liked it.

Neno explained that this is now one of the most desirable residences in the city due to its prime location. People of course now own these units, being given them in Communist times. Neno said that many are now AirBnBs, because Sarajevans can’t afford to rent them.

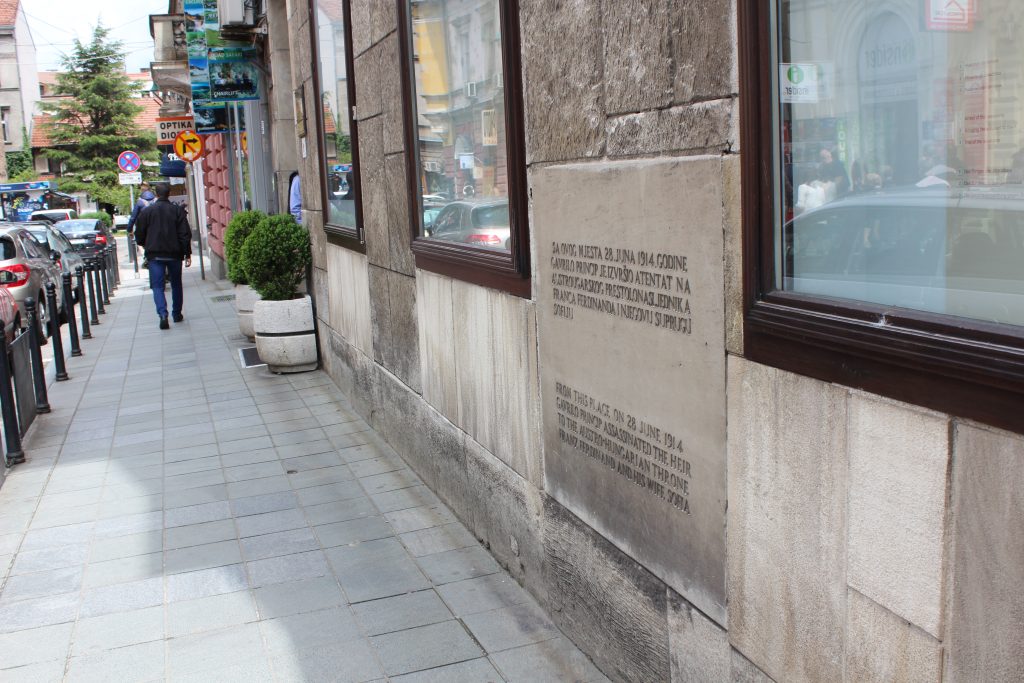

We then walked over to the bridge near where Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie of Austria were shot, which was the catalyst for World War I. Ferdinand wasn’t even the Austrian King, but rather an heir apparent. Neno was clear that if this didn’t start World War I, something else similar would have, which is historically accurate from what I remember of European history. The Balkans were called the “powder Keg” of Europe in that time period, and I would say this rings true even today given the resurgence of ethnic identity and division.

The shooter was a young man named Gavrilo Princip, who was a member of Young Bosnia – essentially a radical terrorist organization composed mostly of Serbs but also of Bosniaks and Croats, whose motives were to unify the Balkans in to Yugoslavia, as well as the Serbian identity. They were also associated with the Black hand, a secret Serbian organization. Gavrilo was one of six other members of the Black Hand tasked and armed with the assassination, and was the only one who succeeded. Although, success didn’t come right away for him.

The assassins were positioning along the opposite bank of the river from where we were standing – across the bridge of the picture you see below (left). The first two failed to act, but the third detonated a bomb that missed Ferdinand’s vehicle and instead injured civilians – this man took his cyanide pill and jumped in to the river. However, the cyanide pill didn’t work and the river was only a few feet deep – he was later beaten by a mob and arrested. Princip was stationed near the bridge in the picture, but was not expecting Ferdinand to continue with his day as planned after a failed attempt at his life just unfolded. However, due to hubris on the part of Ferdinand (Neno’s guess), he continued with his program of a speech at the town hall with Sarajevo’s mayor. After the speech, they did decide to change plans and visit the bomb victims at the hospital instead of going to lunch – but nobody told their driver. The driver at this point should have backtracked along the river the same way he came in, past the area where the first bombing occurred. Instead, he thought they were still going to lunch per the original plan, so he turned right at the street on Latin bridge – where Princip just happened to be waiting at a cafe on the corner. Princip took the opportunity and opened fire, killing both Ferdinand and his wife. You can see the spot just at the corner of the Latin bridge where this went down (on the right).

Ironically, both Princip and the other perpetrator who detonated the first bomb got 20 years in prison, while one of the other conspirators, who was tried as an adult got death by hanging. The death penalty was off the table for anyone under the age of 20, and Princip was just a few weeks shy of his 20th birthday. Princip eventually was transferred to a prison in the Czech Republic, and died after serving three years from tuberculosis. The assassin who detonated the bomb shared a similar fate.

And these are the events that set off World War I – essentially a growing under-current turned violent of pan-Slavic sentiment and desire for unification. The history of Sarajevo is fascinating indeed.

On our next stop, we learned more about the Siege of Sarajevo from 1992 to 1996 during the Balkan War, while walking in front of the Sarajevo beer factory. The Siege of Sarajevo is the longest siege in modern history of a capital city – 1,425 days. I asked Neno why the siege lasted so long. He thinks that the UN presence and the humanitarian aid was partially to blame, since it established a demilitarized zone which was only occasionally violated. Interestingly, under this zone, Sarajevans dug a tunnel to smuggle in weapons for the resistance.

UN sites had previously been targeted and attacked by the Serbians. Seemingly, after the historic marketplace was damaged on several occasions during the Markale Massace, the UN could no longer abide – it ordered NATO air strikes that provided enough resistance for the tide to begin to turn.

This beer factory was one of the reasons the people of Sarajevo were able to withstand the siege. While the Serbian forces cut all the water lines in the city, they did not know that there was a natural spring located underneath the beer factory. This source of fresh water, coupled with food drops from humanitarian aid, allows Sarajevans to withstand the four years underground.

Neno personally recounted what it was like as an 11 year old boy during the war (roughly my age at the time). He made it in to a kind of game – around when you could go outside and when you couldn’t, and how long you should stay out. He spent 4 years basically living in a basement with other families, and every time someone went outside, they risked being shot. The snipers had positions in the hills and in taller buildings in the city, and would shoot anything that moved indiscriminately. It’s estimated that 13,942 people were killed during the siege, and 5,434 were civilians. The road from the city to the airport (the one we drove in on) became known as “Sniper’s Alley.”

Occasionally Neno would venture up the stairs from the basement in the apartment building to his room to exchange a toy, with a set amount of time that he was allowed to be gone. One time, he heard firing right above him, and ran back down. But it still didn’t discourage them every once in a while testing it, and the necessity of water runs made the risk unavoidable. Every time one stepped outside, one faced death.

Yet the Sarajevans resisted, not wanting to give up their city.

School was for a few hours every day and was sporadic, but they tried to live life normally and their lives did go on. When the war ended, Neno was actually upset because it meant he had to go back to actual school – he of course realized this was ridiculous, but he had mentally compartmentalized the four years as camping in the basement, where he could attend school in his pajamas with his friends. It was both astonishing and horrifying, as well as a testament to the human spirit, and/or what it’s easy to get use to, that these survivors resisted. They did just that – survived, and fought for their city. And, even though Serbia was the aggressor here, many Serbians lived in Sarajevo and fought and resisted alongside their neighbors. They were Sarajevans first.

We continued back down to the river to take a look at the “Spite House” – it’s the white house behind the bus in the picture with the lettering written on it. It’s named so because the Austro-Hungarians forced residents to relocate (with compensation) when they began development on the library (picture to the right). One man held out, and demanded that his house be moved brick by brick to the other side of the river. It eventually was. Neno said the lettering on the outside of the house translated roughly in to “house of stubbornness”.

Our final portion of the tour took us back to Ottoman times in the marketplace.

We stopped while Neno explained the significance of the domed building in the background. It was where the silk merchants did business, and it was heavily armored.

We then continued to what the locals call “Pigeon Square.” It was the natural meeting point in the city and a very large, main square. The fountain in the middle provides clean drinking water.

We walked by the mosque and it was seeing a lot of activity today due to Ramadan. Across from the mosque, we stepped in to a courtyard. This was a very significant Ottoman advancement – that of a madrasa, the oldest in the city (16th century), built by governor Gazi Husrev-Bey.

Neno pointed out another curio – see the clock below? It was actually a countdown to how many hours and minutes until sundown to break the fast.

For our last stop, we went inside Morića Han, an inn for traders and travelers during Ottoman times. Each room inside was numbered, and merchants could stay there for free, up to 3 days, in accordance with Muslim tradition. This was another work by Governor Gazi Husrev-Beg who did a lot to better Sarajevo.

Neno ended the tour there, giving us a fabulous overview of the history of Sarajevo. I couldn’t recommend this tour, or this city, more.

[…] about in Bruges. After Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo (which we learned about here), Germany wanted to break Belgian’s neutral position and asked for passage to March through in […]

[…] we decided to set out there again, but this time go farther East – flying to Belgrade, Serbia, While we were in Sarajevo on our past Balkans trip, we had also met a traveler who spoke so highly of Belgrade that we just […]

[…] and how he remembers it so vividly even today. While not has traumatic as what we had heard in Sarajevo, the account was still haunting. Even though his village was on the opposite side of the city […]